Friday 29 January 2010

Read a Lot, Forget Most of What You Read, and Be Slow-witted

I rarely read new books - don't think I read a single one last year - but when Sarah Bakewell's How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer turned up out of the blue at NigeCorp HQ, I jumped on it. The title really should be How to Live? as it's a question - the question - but no doubt the publishers were hoping the book would sell a few more for having a self-help title. A self-help manual is of course the last thing How to Live is. It's a throughly enjoyable and engrossing tour of Montaigne's life and essays, fittingly light-footed, curious and digressive, and, like its subject, chary of answers and certainty. (It's also a handsomely produced volume.) The title of this post is the title of one of the chapters (one of the attempts at an answer), which explores Montaigne's reading, and his claims to extreme forgetfulness and slow wits. It is consoling to think that reading a lot, forgetting most of it and being slow-witted might add up to a good way of living. Maybe, as my memory becomes ever more sieve-like and my wits ever slower, I am making a virtue out of necessity here - or is there something in it? Do forgetfulness and slow wits (and, of course, extensive reading) save us from worse things? Probably they do.

Wednesday 27 January 2010

Geoffrey Hill - Restful?!

For Ronald Firbank, a man of few coherent words, the highest praise he could give a work of art or literature was to describe it as 'very restful'. Now we live in a time where the great assertive cliche about art - used to defend new art and retrospectively to boost older art - is that it is the opposite of restful, that it shakes you up and disturbs you. Clearly this is not definitive, any more than 'very restful' is, but I wonder if we shouldn't be standing up for the restful quality of much of the best art. Think Bach, think Matisse, think Wallace Stevens. Think Geoffrey Hill? Surely not - but the reason I'm writing this is that, in the midst of my current difficulties, I'm settling down at the end of the day in a thoroughly restful way with Hill's The Triumph of Love, a few stanzas of which has me, to my surprise, in a state of mental repose just right for entering the realm of sleep (no, scoffers, he is not actually sending me to sleep). This is odd, as Hill is a notoriously obscure and rebarbative poet, and The Triumph of Love has been described as 'a raw exposed nerve of a work', 'hectoring, philosophical, bitter', 'exacting, academic, unbending' and more in the same vein. It is, after all, the poem in which Hill forces himself to tell us what a poem 'ought to be' - 'a sad and angry consolation'. On the other hand, Elaine Feinstein, describes The Triumph of Love as 'an extraordinarily lucid and often luminous poem' - and that is more like how it strikes me. Not lucid in the sense of easily (or, in some places, at all) understood, but in the sense of at least seeming to carry forward an argument, a process, with a kind of stately clarity of purpose, whatever the bitter and angry notes. Perhaps, in the end, it is simply the conformation of words - the flow of those mighty measures, the epic sweep - that I feel as restful, as they wash over me in my drowsy state...

'So what is faith if it is not

inescapable endurance? Unrevisited, the ferns

are breast-high, head-high, the days

lustrous, with their hinterlands of thunder.

Light is this instant, far-seeing

into itself, its own

signature on things that recognize

salvation. I

am an old man, a child, the horizon

is Traherne’s country.'

That is lucid and luminous enough, surely (and beautiful). Restful? Maybe that's only me, and only this week...

'So what is faith if it is not

inescapable endurance? Unrevisited, the ferns

are breast-high, head-high, the days

lustrous, with their hinterlands of thunder.

Light is this instant, far-seeing

into itself, its own

signature on things that recognize

salvation. I

am an old man, a child, the horizon

is Traherne’s country.'

That is lucid and luminous enough, surely (and beautiful). Restful? Maybe that's only me, and only this week...

Tuesday 26 January 2010

Still Read

A while back, I mentioned as a forgotten giant of English letters Hugh Walpole - now, I assumed, one of the great unreads. Picture my surprise then (no, don't - it was early in the morning and I was not at my best) when on the train I noticed that the damned thick square book the woman opposite me was reading was The Fortress by Hugh Walpole, the second of the Herries Chronicles. The reader, in her 30s I'd say, seemed thoroughly engrossed - and it wasn't a dusty old edition from a charity shop but a very recent reprint. Walpole, it seems, is still read.

Sunday 24 January 2010

Two and a Half Men and One Novel

Sorry the posting has been so scant lately. My working life (roll on its end) is in a peculiarly demanding phase at the moment and, as a result, is occupying far far more of my time, attention and mental activity than is compatible with doing anything much else. Typically, working days have been ending with the wrung-out wreckage of me slumped in front of Comedy Central watching back-to-back Two And A Half Men and wishing it was Frasier. Actually, though, Two And A Half Men is a pretty remarkable sitcom of the 'no hugs, no learning' school. Charlie Sheen plays a rich, sex-addicted sociopath (no typecasting there) who shares his home with his uptight divorced brother - equally sex-obsessed but fiasco-prone - and the brother's weird kid. In the background is the brothers' sex-addicted sociopath mother, and in the foreground, acting as a kind of Chorus, is their sharp-tongued, biker-built housekeeper, the force that actually rules the household and keeps it together. In most episodes the plot revolves around the sexual rivalry of the brothers, culminating in Charlie's invariable routing and humiliation of his sad sap of a brother. See - what's not to like? The fact that it's actually funny says much for the sharpness of the scriptwriting. A British version of this would be utterly witless and unwatchable... So those are my well-spent evenings, followed by coma-like but too brief sleep, then back into the workstorm. On a more exalted level, I have managed to read along the way another William Maxwell, They Came Like Swallows. As short as So Long See You Tomorrow, but from much earlier in Maxwell's career, it is every bit as deft and heartbeakingly precise, with never a word wasted and the author's immersion in his characters and their world total. Set in 1918 during the influenza epidemic, it tells its desperately sad (and semi-autobiographical) story through the eyes of two very different brothers and their father. To say more would be to give too much away to any who haven't read it, but it is a quite extraordinary book, one that is impossible to finish without tears. And now I'm reading more V.S.Pritchett short stories... Life goes on - and will return to something much more liveable and leisurely before long. It can't be too soon. (The picture is in honour of Edouard Manet's birthday yesterday.)

Tuesday 19 January 2010

Such Sad News...

Any Excuse for a Cezanne

And the excuse is that it's his birthday (born 1839), and that this - L'Etang des Soeurs - is a very beautiful painting, before which I've stood many a time in the Courtauld Gallery, and that I'm up to the oxters in work at NigeCorp and my spirits need a lift. So why not share that lift? And, talking of lifting the spirits, the Venice Daily Photo blog is on great form, full of glorious images of Venice in winter.

And the excuse is that it's his birthday (born 1839), and that this - L'Etang des Soeurs - is a very beautiful painting, before which I've stood many a time in the Courtauld Gallery, and that I'm up to the oxters in work at NigeCorp and my spirits need a lift. So why not share that lift? And, talking of lifting the spirits, the Venice Daily Photo blog is on great form, full of glorious images of Venice in winter.

Sunday 17 January 2010

How's About You?

I've been listening to an album, Friend of a Friend, by David Rawlings, long-time collaborator of Gillian Welch (and Ryan Adams), this time in the guise of the Dave Rawlings Machine. Gillian features throughout, as writer and performer, but David is in the foreground. It's a little too patchy to be a great album - you get the impression that without the ferociously driven Gillian in the driver's seat, Rawlings is quite happy to idle (and he's such a damn fine guitarist that it's a pleasure to hear him even when he's not trying). The high point is an extraordinary 'medley' in which Conor Oberst's Method Acting merges into Neil Young's Cortez the Killer (a song in which, by contrast with Oberst's, it's best not to listen to the words). But there's one song that perfectly illustrates the Welch-Rawlings ability to write new songs that sound as if they've been around for ever - it's How's About You?, which anyone would confidently date to 1930 or thereabouts, but is fresh minted by Gillian and David. Enjoy it here - and be warned, it's damnably catchy...

The School Prints

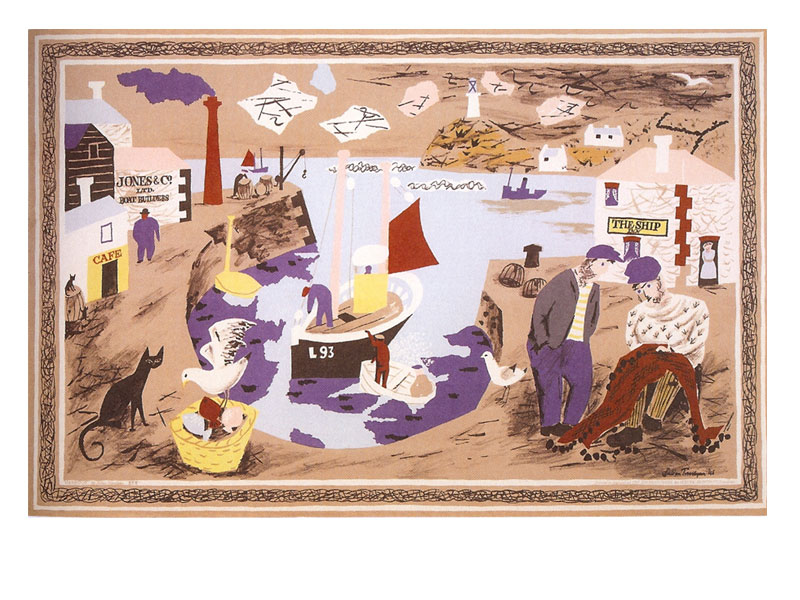

For me, it was Rembrandt's Portrait of His Mother (the one in the Royal Collection), in a black-and-white reproduction in an encyclopaedia. I was 9 or 10 at the time, and this was the first picture I saw that moved me, and gave me an inkling of what a painting can do to a person. Later, at grammar school, I found the main corridor dotted with colour reproductions, faded and cyanosing, among which I remember The Fighting Temeraire, Flatford Mill, a Matisse with a bowl of goldfish, a blue period Picasso. All these tooks me farther along the path, inspiring me to seek out art books at the library, begin my (amateur) education in art, and discover what was to be a major source of pleasure and much more for the rest of my life. What I did not see - and wish I had - in my formative years were the School Prints. These were the brainchild of a remarkable woman, Brenda Rawnsley, arts campaigner, art education activist and wartime WAAF Squadron Officer, who in 1945 took over a company called School Prints Ltd and gave it a new lease of life by getting an impressive roster of contemporary artists to create limited-edition prints which could be sold at low price to schools, giving them a taste of good modern work to sharpen children's appreciation and enjoyment of art. She soon had the likes of John Nash, Julian Trevelyan (that's his jolly Harbour above) and Feliks Topolski signed up, producing characteristic work that made little or no concession to being 'for the children'. These colourful and lively works would at the time have seemed far more avant-garde than they do now, when they have gained a nostalgic period charm. Before long Rawnsley was going international, persuading the likes of Dufy, Matisse, Picasso and Braque to sign up. Sadly, however, the launch of the international series coincided with Sir Alfred Munnings' idiotic but highly influential tirade against Picasso and Matisse at the Royal Academy's 1949 annual dinner. British public opinion naturally swung behind Munnings, and the series flopped, leaving Rawnsley with large numbers of unsold prints and larger debts. This was the end of a brave and brilliant experiment, which must have done much to open the eyes and stir the imaginations of those children lucky enough to have had School Prints on the walls of their school. Rather wonderfully, a lot of them can still be bought (at rather higher prices than Brenda Rawnsley envisaged) - you can see them, with a short account of the School Prints project, here.

For me, it was Rembrandt's Portrait of His Mother (the one in the Royal Collection), in a black-and-white reproduction in an encyclopaedia. I was 9 or 10 at the time, and this was the first picture I saw that moved me, and gave me an inkling of what a painting can do to a person. Later, at grammar school, I found the main corridor dotted with colour reproductions, faded and cyanosing, among which I remember The Fighting Temeraire, Flatford Mill, a Matisse with a bowl of goldfish, a blue period Picasso. All these tooks me farther along the path, inspiring me to seek out art books at the library, begin my (amateur) education in art, and discover what was to be a major source of pleasure and much more for the rest of my life. What I did not see - and wish I had - in my formative years were the School Prints. These were the brainchild of a remarkable woman, Brenda Rawnsley, arts campaigner, art education activist and wartime WAAF Squadron Officer, who in 1945 took over a company called School Prints Ltd and gave it a new lease of life by getting an impressive roster of contemporary artists to create limited-edition prints which could be sold at low price to schools, giving them a taste of good modern work to sharpen children's appreciation and enjoyment of art. She soon had the likes of John Nash, Julian Trevelyan (that's his jolly Harbour above) and Feliks Topolski signed up, producing characteristic work that made little or no concession to being 'for the children'. These colourful and lively works would at the time have seemed far more avant-garde than they do now, when they have gained a nostalgic period charm. Before long Rawnsley was going international, persuading the likes of Dufy, Matisse, Picasso and Braque to sign up. Sadly, however, the launch of the international series coincided with Sir Alfred Munnings' idiotic but highly influential tirade against Picasso and Matisse at the Royal Academy's 1949 annual dinner. British public opinion naturally swung behind Munnings, and the series flopped, leaving Rawnsley with large numbers of unsold prints and larger debts. This was the end of a brave and brilliant experiment, which must have done much to open the eyes and stir the imaginations of those children lucky enough to have had School Prints on the walls of their school. Rather wonderfully, a lot of them can still be bought (at rather higher prices than Brenda Rawnsley envisaged) - you can see them, with a short account of the School Prints project, here.

Saturday 16 January 2010

Two Butterfly Lives

As anticipated, that handsome volume The Aurelian Legacy: British Butterflies and Their Collectors has proved good bedtime reading to get me through the lepidopteral close season. Like Gaul, it is divided into three parts - a history of the British butterfly fancy, a biographical dictionary of notable butterfly men and women, and essays on some of the more historically interesting of our butterflies. Lately I've been browsing in the biographies, which is where I found the chap with the zebra cart above - Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild of Tring, who sounds like a delightfull fellow. Temperamentally unsuited for the normal occupations of the world, he devoted himself entirely to building up the largest collection of animals ever assembled by one man - everything from starfish to gorillas and giant tortoises (144 of them), with butterflies and moths to the number of 100,000 species, with the greatest range of variants ever seen ('I have no duplicates,' he declared). As a student at Cambridge, he kept a much-loved flock of kiwis, and kangaroos, ostriches and, of course, zebras roamed free in his grounds at Tring. He once rode a zebra carriage and four through Piccadilly to Buckingham Palace. Such exhibitionism is often a product of shyness, and Rothschild was cripplingly shy. He was also apparently unable to control his voice, which alternated quite unpredictably between a low stammer and a loud bellow. He grew very stout, tipping the scales at 22 stone, his vast 6ft 3in body balanced on tiny feet, giving the effect, when he bowled around his mansion, of (in his niece Miriam's words) 'a grand piano on castors'. His younger brother, Charles, was also a collector (and a pioneer of nature conservation) but his main interest was in fleas, on which he became - like his daughter Miriam - a world authority.

As anticipated, that handsome volume The Aurelian Legacy: British Butterflies and Their Collectors has proved good bedtime reading to get me through the lepidopteral close season. Like Gaul, it is divided into three parts - a history of the British butterfly fancy, a biographical dictionary of notable butterfly men and women, and essays on some of the more historically interesting of our butterflies. Lately I've been browsing in the biographies, which is where I found the chap with the zebra cart above - Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild of Tring, who sounds like a delightfull fellow. Temperamentally unsuited for the normal occupations of the world, he devoted himself entirely to building up the largest collection of animals ever assembled by one man - everything from starfish to gorillas and giant tortoises (144 of them), with butterflies and moths to the number of 100,000 species, with the greatest range of variants ever seen ('I have no duplicates,' he declared). As a student at Cambridge, he kept a much-loved flock of kiwis, and kangaroos, ostriches and, of course, zebras roamed free in his grounds at Tring. He once rode a zebra carriage and four through Piccadilly to Buckingham Palace. Such exhibitionism is often a product of shyness, and Rothschild was cripplingly shy. He was also apparently unable to control his voice, which alternated quite unpredictably between a low stammer and a loud bellow. He grew very stout, tipping the scales at 22 stone, his vast 6ft 3in body balanced on tiny feet, giving the effect, when he bowled around his mansion, of (in his niece Miriam's words) 'a grand piano on castors'. His younger brother, Charles, was also a collector (and a pioneer of nature conservation) but his main interest was in fleas, on which he became - like his daughter Miriam - a world authority.Here's another brief life - of a fat, genial chap, bearded and jug-eared, who is photographed reclining on one elbow in a meadow, looking more like a farm worker enjoying a break than the successful tax accountant, first-class shot and fly fisherman and eminent butterfly collector that he was. This is Robert 'Porker' Watson (1916-84), who began life selling rabbits, running a paper round, then a milk round, and winning wrestling prizes at fairs. How he made the transition from milkman to tax accountant is not clear, and his love life too hints at mysteries, including as it did four marriages and a remarriage. He named the house he built 'Porcorum'. In his butterfly collecting, he aimed for a collection of perfect specimens, and 'his setting was described as a miracle of perfection, despite his being virtually blind in one eye'. It is a wonderful world, the world of the butterfly fanciers, and The Aurelian Legacy is an endlessly rewarding guide to it.

Tuesday 12 January 2010

Accidental Birth of the Haikette

Inspired by the unprecedented response (hem hem) to my sawn-off haiku encapsulating the Noughties, I've decided to regularise the form and give it a name. It shall be called the Haikette (with grateful acknowledgment to the Sage of Tiverton, whom God preserve), and it shall consist of 13 syllables, arranged thus:

4

6

3

That's enough syllables for anyone. Here's an example:

Gulls on the ice.

Seared rushes fringe the lake.

My breath, smoke.

(It should be centred, rather than ranged left, but I can't work out how to do it on Blogger.)

That's a memory of yesterday, when I walked out in quest of waxwings, not really expecting to find any - and I didn't. That magical sighting from a passing train will stand alone in my memory (albeit with a butterfly relative). I did, however, get a good look at another beautiful tree sparrow, and thought of my daughter, now back in New Zealand...

4

6

3

That's enough syllables for anyone. Here's an example:

Gulls on the ice.

Seared rushes fringe the lake.

My breath, smoke.

(It should be centred, rather than ranged left, but I can't work out how to do it on Blogger.)

That's a memory of yesterday, when I walked out in quest of waxwings, not really expecting to find any - and I didn't. That magical sighting from a passing train will stand alone in my memory (albeit with a butterfly relative). I did, however, get a good look at another beautiful tree sparrow, and thought of my daughter, now back in New Zealand...

Sunday 10 January 2010

A Waxwing Winter?

It's not only redwings and fieldfares that are invading in vast numbers this icy winter (in Kent yesterday I saw an orchard entirely filled with a mixed flock of these, perching on every branch of every tree), it looks as if it might also be a waxwing winter. This unmistakable visitor from the forests of eastern Europe is extremely partial to the berries of the rowan, as well as pyracantha, cotoneaster and their like - just the kind of sturdy vegetation favoured by the planners of car parks and shopping centres. This means that when waxwings are around, you might well see them in such unexpected places - and, being unused to humans, they're surprisingly tame and tend to carry on feeding regardless. Cut to this morning, and there I was on my usual Sunday morning train in to work, gazing drowsily out of the window (it had been quite a day down in Kent) before getting down to a book, when I saw it - my first waxwing! The train was past it in a second, but there was no mistaking what it was, especially as it was feeding greedily on a rowan right by the track and seemed untroubled by the passing train. If waxwings have reached my part of south London/Surrey, this must surely be a waxwing winter! Tomorrow I intend to go out searching, in the hope of getting a much longer look at this extraordinary bird.

It's not only redwings and fieldfares that are invading in vast numbers this icy winter (in Kent yesterday I saw an orchard entirely filled with a mixed flock of these, perching on every branch of every tree), it looks as if it might also be a waxwing winter. This unmistakable visitor from the forests of eastern Europe is extremely partial to the berries of the rowan, as well as pyracantha, cotoneaster and their like - just the kind of sturdy vegetation favoured by the planners of car parks and shopping centres. This means that when waxwings are around, you might well see them in such unexpected places - and, being unused to humans, they're surprisingly tame and tend to carry on feeding regardless. Cut to this morning, and there I was on my usual Sunday morning train in to work, gazing drowsily out of the window (it had been quite a day down in Kent) before getting down to a book, when I saw it - my first waxwing! The train was past it in a second, but there was no mistaking what it was, especially as it was feeding greedily on a rowan right by the track and seemed untroubled by the passing train. If waxwings have reached my part of south London/Surrey, this must surely be a waxwing winter! Tomorrow I intend to go out searching, in the hope of getting a much longer look at this extraordinary bird.

Friday 8 January 2010

Any Excuse for a Saucy Painting...

Thursday 7 January 2010

You Can't Budge a Carp

The farcical Hoon-Hewitt coup that wasn't provided much amusement yesterday. When will these people realise there's no budging Broon? The man has the uncannily prehensile feet and 'almost imperceptible arches' of the young Augustus Carp (and the capacity for moral humbug and self-delusion of the adult Augustus Carp Esq).

Wednesday 6 January 2010

Compensations

Ah well, this wintry weather has its compensations. There's the cheering beauty of untrodden snow, of course - and of hoarfrost, which was spectacular when I was in Oxfordshire the other day: every twig of every tree white with it, every green leaf fringed with fine silver whiskers... And there are the welcome unfamiliar birds that fly in with the cold. On Monday in the park I saw a couple of bramblings, a pretty kind of winter chaffinch with an air of the pine forest about it - a while since I saw any in my locality. And on Saturday I had my binoculars trained for a long time on a solitary fieldfare (so beautifully marked in grey, chestnut and black). As for the redwings, they are so numerous down my way this year that they're second only to the crows and gulls (make that third then) - a sure sign of a hard winter. If the Met Office had occupied itself looking out for redwings, it might not have issued its confident forecast of a 'mild winter'.

Ah well, this wintry weather has its compensations. There's the cheering beauty of untrodden snow, of course - and of hoarfrost, which was spectacular when I was in Oxfordshire the other day: every twig of every tree white with it, every green leaf fringed with fine silver whiskers... And there are the welcome unfamiliar birds that fly in with the cold. On Monday in the park I saw a couple of bramblings, a pretty kind of winter chaffinch with an air of the pine forest about it - a while since I saw any in my locality. And on Saturday I had my binoculars trained for a long time on a solitary fieldfare (so beautifully marked in grey, chestnut and black). As for the redwings, they are so numerous down my way this year that they're second only to the crows and gulls (make that third then) - a sure sign of a hard winter. If the Met Office had occupied itself looking out for redwings, it might not have issued its confident forecast of a 'mild winter'.

Epiphanius

Not a name you often hear these days - but a glorious one, and apt for today (Epiphany). Church crawlers will know it as that of one of the finest and most mysterious monumental sculptors of his time (a very few years after Shakespeare's), Epiphanius Evesham. Little is known of his life - not much more than this really - and his works are few and far between (and mostly attributed), but nearly all are of quite extraordinary quality, elegantly and truthfully done. (The picture shows a monument - attributed - in St Bartholomew, Quorn.) My old English master, whom I've mentioned many a time before, was mildly obsessed with the enigmatic figure of Evesham, and would make a special journey to an out-of-the-way church just to see one of his works, however uncertainly attributed. A writer in the Peter Ackroyd line could probably make something of the Evesham mystery; the title's ready-made - Epiphanius.

Not a name you often hear these days - but a glorious one, and apt for today (Epiphany). Church crawlers will know it as that of one of the finest and most mysterious monumental sculptors of his time (a very few years after Shakespeare's), Epiphanius Evesham. Little is known of his life - not much more than this really - and his works are few and far between (and mostly attributed), but nearly all are of quite extraordinary quality, elegantly and truthfully done. (The picture shows a monument - attributed - in St Bartholomew, Quorn.) My old English master, whom I've mentioned many a time before, was mildly obsessed with the enigmatic figure of Evesham, and would make a special journey to an out-of-the-way church just to see one of his works, however uncertainly attributed. A writer in the Peter Ackroyd line could probably make something of the Evesham mystery; the title's ready-made - Epiphanius.

Monday 4 January 2010

Marianne Moore - Fun!

I don't know what it was with me and Marianne Moore. For years I kept meaning to read her 'properly'. I knew her from such gems as Poetry (who could resist that opening line?) and a few others, but I'd never looked further. I was daunted by the Collected Poems, which seemed too hefty a volume for such a springy and light-footed poet - so I was delighted recently to get my hands on the Faber Selected Poems (courtesy of the excellent AbeBooks), an elegant and beautifully designed little volume, which I am enjoying quite tremendously, loving particularly her deft illuminating way with the natural world. The selection opens with the wonderfully breezy The Steeple-Jack - after which what can you do but read on?... And this little volume has her Notes too, which are a joy in themselves: the notes to Tom Fool In Jamaica (Tom Fool was a famous racehorse) are a great deal longer than the poem, and contain another one, by Mme Boufflers, called Sentir avec Ardeur, which begins

I don't know what it was with me and Marianne Moore. For years I kept meaning to read her 'properly'. I knew her from such gems as Poetry (who could resist that opening line?) and a few others, but I'd never looked further. I was daunted by the Collected Poems, which seemed too hefty a volume for such a springy and light-footed poet - so I was delighted recently to get my hands on the Faber Selected Poems (courtesy of the excellent AbeBooks), an elegant and beautifully designed little volume, which I am enjoying quite tremendously, loving particularly her deft illuminating way with the natural world. The selection opens with the wonderfully breezy The Steeple-Jack - after which what can you do but read on?... And this little volume has her Notes too, which are a joy in themselves: the notes to Tom Fool In Jamaica (Tom Fool was a famous racehorse) are a great deal longer than the poem, and contain another one, by Mme Boufflers, called Sentir avec Ardeur, which begins Il faut dire en deux mots

Ce qu'on veut dire;

Les longs propos

Sont sots...

For all her apparent profligacy and luxuriance, Moore says it all en deux mots. Here's a wonderful short poem:

A Face

'I am not treacherous, callous, jealous, superstitious,

supercilious, venomous or absolutely hideous':

studying and studying its expression,

exasperated desperation

though at no real impasse,

would gladly break the glass;

when love of order, ardour, uncircuitous simplicity

with an expression of inquiry, are all one needs to be!

Certain faces, a few, one or two - or one

face photographed by recollection -

to my mind, to my sight,

must remain a delight.

Moore is to me one of those poets who seem to fill the world, and the business of living, with so many more possibilities and so much less ponderous necessity. Yes she is even (see photo).... fun!

Sunday 3 January 2010

August Macke

I don't know about you, but for myself I'm still in the state of drowsy mental torpor that goes with cold weather and a long (though in my case work-punctuated) Christmas break. Today I stirred sufficiently to note that it's the birthday of the German painter August Macke (born in 1887). Macke's best-known works are his joyous semi-abstract semi-expressionist paintings inspired by the light and colour of Tunisia (they sometimes even turn up as greetings cards). The beautifully modulated and balanced work above - Abschied (Farewell)- is lit by a colder northern light and strikes a more sombre note. It was in fact the last painting he finished, before his death on the front, at Champagne, in the second week of World War I. As always with such brutally early deaths of gifted artists, you wonder what more he might have achieved...

I don't know about you, but for myself I'm still in the state of drowsy mental torpor that goes with cold weather and a long (though in my case work-punctuated) Christmas break. Today I stirred sufficiently to note that it's the birthday of the German painter August Macke (born in 1887). Macke's best-known works are his joyous semi-abstract semi-expressionist paintings inspired by the light and colour of Tunisia (they sometimes even turn up as greetings cards). The beautifully modulated and balanced work above - Abschied (Farewell)- is lit by a colder northern light and strikes a more sombre note. It was in fact the last painting he finished, before his death on the front, at Champagne, in the second week of World War I. As always with such brutally early deaths of gifted artists, you wonder what more he might have achieved...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)